- Home

- Ransom Riggs

The Conference of the Birds Page 5

The Conference of the Birds Read online

Page 5

The room was lined with thick fur rugs, and the only furniture was a pile of pillows on the floor. Miss Peregrine walked to a cloudy window and looked out for what seemed like a long time.

“I should’ve known you’d do this,” she began. “It’s my fault, really, for leaving you alone and unguarded.” She shook her head. “It’s just what your grandfather would have done.”

“I’m sorry for any trouble I caused,” I said. “But I’m not sorry for—”

“Trouble can be handled,” she interrupted. “But we could not handle losing you.”

I’d been all ready to argue, to make an impassioned case for why I’d gone to help H rescue Noor from Leo Burnham, and she’d caught me off guard.

“Then you’re not . . . angry?”

“Oh no. I am livid. But I learned long ago to control my emotions.” She turned fully to face me, and I saw that her eyes were rimmed with tears. “It’s good to have you back, Mr. Portman. Never do anything like that again.”

I nodded, choking back tears of my own.

She cleared her throat, rolled her shoulders, and reset her expression. “Now, then. You are going to sit down and tell me everything. I believe you were saying something about how you had to do this.”

There was a sharp knock at the door, and without waiting for an answer, it opened.

Noor came inside.

Miss Peregrine frowned. “I’m sorry, Miss Pradesh. We’re having a private conversation. Jacob has something to tell me.”

“There’s something he and I need to talk about.” She pinned me with her eyes. “This prophecy. You made it sound urgent.”

“What prophecy?” Miss Peregrine said sharply.

“Apparently it’s got something to do with me,” Noor said. “So I’m sorry, but I can’t let someone else hear about it before I do.”

Miss Peregrine looked both surprised and impressed. “I completely understand. I suppose you’d better come in.”

She gestured to a pillow on the floor.

* * *

◆ ◆ ◆

We settled among the pillows. Miss Peregrine looked regal even sitting on the floor, back straight and her hands lost in the black folds of her dress. I told her and Noor about the prophecy, or what I’d heard of it, anyway, and what had preceded its telling. I caught Miss Peregrine up on some details she didn’t yet know, such as how I’d snuck out of the Panloopticon to find H in New York and what I’d found when I reached his apartment: Noor sleep-dusted on H’s sofa; H mortally wounded on the floor.

Then I told them what he’d said to me just before he died.

I wished now that I had written down his exact words while they were still fresh in my mind; so much had happened since they were told to me that they were becoming a bit jumbled.

“H said there was a prophecy that foretold your birth,” I said, looking at Noor. “You were ‘one of the seven’ who would be the ‘emancipators of peculiardom.’”

She looked at me like I was speaking Greek. “What’s that supposed to mean?”

“I don’t know,” I said, and looked hopefully to Miss Peregrine.

Her expression was neutral. “Is there more?”

I nodded. “He said a ‘new and dangerous age’ was coming, which I guess is what the seven are supposed to ‘emancipate’ us from. And he said the prophecy was the reason those men were hunting Noor.”

“You mean the weirdos who were stalking me at school,” said Noor.

“Yeah. And who came after us at that building site in the helicopter. And shot Bronwyn with the sleep dart.”

“Hmmm.” Miss Peregrine seemed doubtful.

“Well?” I said to Noor. “What do you think?”

“That’s it?” Noor’s eyebrows rose. “That’s the whole thing?”

“Highly unlikely,” Miss Peregrine said. “It sounds like H was paraphrasing. Attempting to convey the basics to you before he bled to death.”

“But what does any of that mean?” Noor said to Miss Peregrine. “Bronwyn said you’re someone who knows things.”

“I am, generally. But obscure prophecies are not my area of expertise.”

They were, however, one of Horace’s. And so, with Noor’s permission, we called him into the room and told him about it.

He listened with intense fascination. “The seven emancipators of peculiardom,” he said, rubbing a hand over his smooth chin. “It rings a bell, but I need more information. Did he say who the prophet was? Or where the prophecy came from?”

I struggled to remember. “He said something about an”—the exact word was escaping me now—“an . . . Apocryphate? Apocryton?”

“Interesting,” Horace said, nodding. “Sounds like a text of some kind. Not one I’ve heard of, but it’s something to go on.”

“Is that all?” Miss Peregrine said. “H paraphrased a few lines of prophecy and then expired?”

I shook my head. “No. The last thing he said was that I should take Noor to find a woman named V.”

“What?”

We turned to see Emma poking her head through the door. She put a hand over her mouth, embarrassed at her outburst, then decided to own it and just came in. “Sorry. But we’ve all been listening.”

The door opened wider, and there were all my friends on the other side.

Miss Peregrine let out an irritated sigh. “Oh, come in, then,” she said. “I’m sorry, Noor. There really are no secrets amongst us, and I have a feeling this may be a matter that will concern all of us.”

Noor shrugged. “If anyone can tell me what the hell this all means, I’d write it on a billboard.”

“An emancipator of peculiardom, huh?” said Enoch. “Sounds quite fancy.”

I gave him an elbow in the ribs as he sat down next to me. “Don’t start with her,” I muttered.

“Wasn’t my idea,” Noor said to Enoch. “I think it sounds nuts.”

“But H must’ve believed it,” said Millard, his purple jacket pacing the floor, “or he wouldn’t have risked his life to save Noor’s. And he wouldn’t have roped Jacob and the rest of us into helping find her.”

“You were saying,” Emma said to me. “About that . . . woman.”

“V, yes,” I said. “She’s the last hollow-slayer left alive, H said. She was personally trained by my grandfather back in the sixties. There are references to her all through his mission logs.”

“The diviners remembered meeting her more than once,” said Bronwyn. “They seemed quite impressed with her.”

Emma squirmed, unable to hide her unease.

Miss Peregrine drew a small pipe from her dress pocket and asked Emma to light it for her, then took a deep draw and let out a puff of green smoke. “I find it very curious,” she said to me, “that he advised you to seek the help of another hollow-hunter, rather than an ymbryne.”

Rather than me.

“Very curious,” Claire agreed.

“He seemed to think V was the only person who could help us,” I said. “But he didn’t say why.”

Miss Peregrine nodded and blew out another green puff. “Abe Portman and I respected each other immensely, but there were a number of matters on which his organization and mine disagreed. It’s possible he simply felt more comfortable sending you into the protection of one of his comrades, rather than me.”

“Or he believed there were things you didn’t know about the situation,” said Millard.

“Or the prophecy,” said Horace, and Miss Peregrine looked briefly annoyed at the reminder.

I knew, of course, that H did not fully trust the ymbrynes, but he had never explained why, and it wasn’t something I was prepared to bring up in front of the others.

“He left us a map,” said Noor. “To find V.”

“A map?” said Millard, spinning to face her. “Do tell.”

/> “Just before he died, H directed his hollowgast, Horatio, to give us a piece of a map from a wall safe,” I said. “Then he let Horatio eat his eyes”—this prompted a disgusted groan from several of my friends—“which seemed to allow the hollow to consume his peculiar soul. A few minutes later, he started turning into, I don’t know, a wight, I guess. Or the beginnings of one.”

“And that’s when I woke up,” said Noor. “And Horatio told us something that sounded like a clue.”

“Then he jumped out the window,” I said.

“May I see that map?” said Miss Peregrine.

I handed it to her. Millard’s jacket bent over Miss P’s shoulder as she smoothed the fragment against her leg, and the room went quiet.

“This scrap isn’t much to go on,” Millard said after only a few seconds of study. “It’s a tiny detail of a much larger document, which is mostly topographical.”

“Horatio’s clue sounded like map grid coordinates,” I said.

“Those might help more if we had the whole map,” said Millard. “Or if the map included place names. Towns and roads and lakes.”

“Actually,” said Miss Peregrine, bending closer while holding up a magnifying monocle to one eye, “they appear to have been erased.”

“Curiouser and curiouser,” said Millard. “You say the ex-hollow uttered something . . . what was it?”

“He told us we could find her in a loop,” I said. “H called it ‘the big wind,’ and Horatio said it was ‘in the heart of the storm.’”

“Does that mean anything to you?” Noor said to the room generally.

“Sounds like a looped hurricane, or a cyclone,” said Hugh.

“Obviously,” said Millard.

“What kind of mad ymbryne would loop such a terrible thing?” Olive said.

“One who really doesn’t want visitors dropping in,” said Emma, and Miss Peregrine nodded in agreement.

“Do you know of such a place?” Emma asked her.

Miss Peregrine frowned. “I don’t, sorry to say. It’s probably hidden somewhere in America. Again—not my area of expertise.”

“It will be someone’s,” said Millard. “Don’t despair, Miss Pradesh. We’ll make sense of this yet. May I borrow this?” The map appeared to float as he held it up.

I looked at Noor and she nodded. “Okay,” I said.

“If I can’t crack it, I’ll bet someone around here can.”

“I hope so,” said Noor. “When you go asking around, I’d like to come.”

“Of course,” said Millard, sounding pleased.

“And I can help you find out more about the prophecy,” said Horace.

“You might speak to Miss Avocet,” Miss Peregrine said. “I was her pupil once upon a time, and I remember she had a special interest in lunacy, divination, and automatic writing. Prophetic texts might fall under that aegis.”

“Fantastic idea,” said Horace, his eyes gleaming excitedly. He cocked his head at Miss Peregrine. “Though it would help if I could get off cleaning duty for a few days . . .”

“All right.” The headmistress sighed. “In that case, you’re excused from work, too, Millard.”

“That hardly seems fair!” Claire whined.

“I’m sure I could be of help,” Enoch said with a grin. “Perhaps we should interview the recently deceased H?”

I remembered the dead man packed in ice that Enoch had helped us question back on Cairnholm and shuddered. “No, thanks, Enoch,” I said. “I would never do that to him.”

He shrugged. “I’ll think of something.”

Everyone was chattering in low voices now, until Noor got to her feet and cleared her throat. “I just wanted to say thanks,” she said. “I’m brand-new here, so I don’t know if this sort of thing happens a lot or not . . . prophecies and kidnappings and mysterious maps . . .”

“Not very often,” said Bronwyn. “We went almost sixty years without much happening at all.”

“Then . . . thanks,” she said, a bit awkward.

She was blushing as she sat down.

“Any friend of Jacob’s is a friend of ours,” said Hugh. “And this is how we treat friends.”

There was a chorus of assent. And suddenly I felt very humbled, and very grateful, to have such friends as these.

After a while Miss Peregrine announced that it was dinnertime, and that we’d done a not-very-good job of hosting Noor thus far, and here was our chance to make up for it. We trooped through the house and up the rickety stairs to a dining room, where a long table made from rough planks was set with mismatched cups and plates and a set of windows that looked out onto the polluted river and the crumbling buildings on its opposite bank. In the amber glow of sunset it looked almost pretty.

Noor and I had, finally, a chance to wash up. In the next room there was a basin and a big pitcher of water beneath a cloudy mirror, and we were able to splash some water on our faces and clean ourselves up a bit.

But just a bit.

When we came back, Noor sat beside me, and Emma was lighting candles with her fingertip while Horace oversaw the distribution of food, ladled into bowls from a big black cauldron hanging in the hearth.

“I hope you like stew,” he said, setting a steaming bowl before Noor. “The food’s great in Devil’s Acre, so long as you like stew for every meal.”

“I’d eat anything right now,” she said. “I’m starving.”

“That’s the spirit!”

We settled into easy conversation, and soon the room was filled with the hum of voices and the clatter of spoons. It was remarkably cozy, considering where we were. Making inhospitable places cozy was one of Miss Peregrine’s many talents.

“What did you used to do in your normal life?” asked Olive through a full mouth.

“Go to school, mostly,” Noor replied. “By the way, your use of the past tense there is interesting. . . .”

“Everything’s going to change for you,” Miss Peregrine said.

“It already has,” Noor said. “My life is unrecognizable from what it was last week. Not that I’d really want to go back.”

“That’s precisely it,” said Millard, jabbing a loaded fork in her direction. “It’s very difficult to tolerate a normal life once you’ve lived a peculiar one for a while.”

“Trust me, I’ve tried,” I said.

Noor looked at me. “Do you ever miss your normal life?”

“Not even a little,” I said. And I almost meant it.

“Do you have a mother and father who will miss you?” asked Olive. Olive was always asking about mothers and fathers. I think she missed hers more than anyone, though she had long since outlived them.

“I’ve got foster parents,” said Noor. “I never met my real ones. But I’m sure Fartface and Teena won’t cry too much if I don’t come back.”

The word fartface prompted a few curious glances, but they must have assumed it was just a weird present-day people name, because no one said anything.

“How do you like being peculiar?” asked Bronwyn.

Noor had hardly been able to take a bite of food, but she didn’t seem to mind. “It was scary before I knew what was happening to me, but I’m starting to adjust.”

“Already?” said Hugh. “Back in the Untouchables’ loop—”

“I have a thing about certain types of confined spaces,” she said. “That, uh, door—” She shook her head ruefully. “Kind of threw me for a loop.”

“Threw you for a loop!” Bronwyn shouted, laughing loudly and clapping her hands. “That’s very good!”

Enoch groaned. “No loop puns, please, intentional or otherwise.”

“Sorry,” Noor mumbled, having used the interruption to finally get some food into her mouth. “Unintentional.”

Horace stood up and announced that it was time for des

sert, and he whisked off into the kitchen and brought out a big cake.

“Where did that come from?” Bronwyn cried. “You’ve been holding out on us!”

“I was saving it for something special,” he said. “I think this more than qualifies.”

He served Noor the first slice. Before she could take a bite, he asked her, “When did you realize you were different?”

“I’ve been different my whole life,” Noor said with a subtle smile, “but I only realized I could do this a few months ago.” She waved her hand over a candle, took its light between two fingers, and popped it into her mouth. Then she blew it out again like a long stream of glowing smoke, which slowly settled, like falling particles of dust, back atop the candle.

“How wonderful!” Olive cheered, as everyone oohed and clapped.

“Do you have normal friends?” asked Horace.

“One. Though I think I like her so much because she isn’t very normal.”

“How is Lilly?” Millard asked, a little sigh of longing escaping him.

“I haven’t seen her since you did.”

“Oh,” he said, chastened. “Of course. I hope she’s well.”

Emma, who’d been uncharacteristically quiet, suddenly asked, “Do you have a boyfriend?”

“Emma!” said Millard. “Don’t pry.”

Emma went red and looked down at her cake.

“It’s okay,” said Noor, laughing. “No, I don’t.”

“Guys, I think we should give her a chance to take a few bites,” I said, weirdly embarrassed by Emma’s question.

Miss Peregrine, who had been quietly brooding for the past few minutes, dinged her glass and asked for everyone’s attention. “I’m due back at the peace talks tomorrow,” she said. “The ymbrynes are in the midst of very sensitive negotiations with the leaders of the three American clans”—she gravely directed this to Noor—“and the threat of war between them grows with each passing day. I’m sure H’s brazen rescue and your disappearance have only made things more complicated.”

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children Hollow City

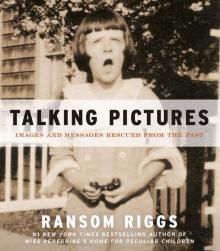

Hollow City Talking Pictures: Images and Messages Rescued From the Past

Talking Pictures: Images and Messages Rescued From the Past Tales of the Peculiar

Tales of the Peculiar The Desolations of Devil's Acre

The Desolations of Devil's Acre Library of Souls

Library of Souls A Map of Days

A Map of Days Hollow City: The Second Novel of Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children

Hollow City: The Second Novel of Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children Talking Pictures

Talking Pictures