- Home

- Ransom Riggs

The Conference of the Birds (Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children) Page 3

The Conference of the Birds (Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children) Read online

Page 3

I said, “I can’t prove you’re not dreaming. But I do know what you’re going through.”

Bronwyn was running back toward us now and mouthing, Come on, come on, come on.

The fence rattled behind us, and someone swore. Then another voice said, “I know there’s a way through here somewhere,” and someone else grunted in reply.

It was a couple of Leo’s guys. They had tracked us all this way.

If Noor had been contemplating some other course of action, that rattling fence banished it from her mind.

We raced through the high grass with Bronwyn and Hugh, up the steps past signs that blurred in my vision but said things like CONDEMNED PROPERTY and NO TRESPASSING, to an entrance that had been boarded over and broken open again. The splintered wood and bent nails gnawed at us like teeth as we contorted ourselves into the breach, once more to be entombed in a place we might never leave.

* * *

◆ ◆ ◆

The building was so dark and packed with trash that we couldn’t quite run, not without impaling ourselves on some sharp obstacle or tripping into a hole in the floor, so instead we scurried sideways like crabs, taking long, kicking steps and sweeping our arms in front of us, following Hugh and Bronwyn. They were familiar with this place. We could hear Leo’s guys in the yard, coming through the fence, pounding up the steps. Bronwyn had blocked the hole through which we’d entered by shoving an old fridge in front of it—it seemed to have been left close by for just that purpose—but we knew that wouldn’t slow Leo’s guys for long.

We stumbled into a large room lit by filthy, half-boarded windows, where we could finally see. We dodged moldering wheelchairs and nightmarish hulks of rusting medical equipment, our feet splashing through a shallow sea of toxic-looking water that stretched from wall to wall.

Noor was humming quietly to herself. I glanced at her, and she stopped.

“Nervous habit,” she said.

I hopscotched around a patch of caved-in floor, then held out my hand to help her across. “What’s there to be nervous about?” I said, managing a mirthless grin.

She took my hand and leapt. She wasn’t laughing. “Please tell me there’s a back way out of here.”

“Better than that,” said Hugh over his shoulder. “It’s a Panloopticon door.”

Before Noor could reply, there came a sound so eerie and out of place it sent shivers through me: a sour, dissonant chord of unmusical music. Rounding a stack of sodden yellow mattresses, we saw where it had come from: a gutted piano. It was an upright model that had been knocked onto its back and lay blocking the room’s only exit, to a hallway lined with doors. The piano’s intestines had been ripped out and nailed to points all around the hallway entrance, the heavy strings rising like a forest of metal hair standing on end. To get out of this room we would have to climb over the piano and squeeze through the strings. Someone had done it already—that must have been the awful chord we’d heard—which meant that that someone had just left this room or was in it with us now.

And then, out from behind a tipped-over baby incubator not far away, a figure rose to standing.

“Ah. It’s you.”

His face was covered by a mat of hair so thick it could only be called fur, and he gave us a cockeyed grin.

It was Dogface.

“Back so soon?” he said to Bronwyn and Hugh.

“Yes, but we can’t stay,” said Bronwyn.

“We need to get out now,” said Hugh.

Dogface leaned against the piano. “Exit fee is two hundred.”

“You said the fee was round-trip!” Hugh said angrily.

“You must have misheard me. You did seem to be in an awful hurry when I was explaining our pricing . . .”

We heard a distant shout, then the scrape of metal against stone. They were starting to move the refrigerator.

Dogface tipped his head toward the sound. “What’s that? You haven’t gotten yourselves into trouble, have you?”

“Yeah,” I said irritably, “there’s someone chasing us.”

“Oh no,” he said, clicking his tongue at me. “That’s going to cost you a bit extra. We’ll have to deceive them, cover for you . . . and are those Leo Burnham’s flunkies? They sound angry.”

“Fine. Whatever it costs,” said Bronwyn.

We were dying to just knock him out of the way, but we knew he could cause us endless trouble if he wanted to.

“Five hundred,” said Dogface.

Another scraping sound, this one longer than the last. They were making progress.

“I only have four hundred,” said Hugh, digging in his pocket.

“Too bad.” Dogface turned to go.

“We’ll pay you tomorrow!” said Bronwyn.

Dogface turned back. “Tomorrow it’ll be seven hundred.”

There was a loud, splintering crash. They’d broken through.

“Okay! Fine!” Hugh said, an agitated bee escaping his lips.

“And don’t be late with it. I’d hate to have to show them your little secret door.”

They paid him all they had. Dogface counted it with excruciating exactness, then stuffed the bills into his pocket. He climbed onto the piano, pulled a lever inside it, then slipped silently through the muted strings. We followed, and when we’d reached the other side, he pushed the lever back into place.

The piano, I realized, was an alarm.

Dogface showed us the way. We rushed after him down a long hall—now that he’d extorted us, he started picking up the pace—but the hallway seemed to stretch on forever.

Along the way, a clutch of peculiars filed out from one of the doorways and began to follow us. They were unusual-looking, even by peculiar standards, and when Noor saw them she drew a sharp breath. A woman who was either legless or whose legs were invisible wafted after us on a cushion of air, the bottom of her long coat fluttering in the vacancy. “Aw, sweetheart, we’re not gonna hurt you,” she said, her voice soft and melodious. “We’ll be friends.”

“Don’t know about friends,” snorted a girl who was at least half warthog, two tusks and a snout protruding from her face, “but if you pay good, we won’t be enemies.”

Then came another legless lady—this one apparently unable to float, because she moved by taking great leaps forward on her hands. Then, with the litheness of a cat she jumped into the burly warthog girl’s waiting arms. I could see her properly there: She lacked not only legs, but hips, waist, and half a torso. Her body, and the black satin blouse she wore, were cropped in a neat line near her belly button.

“Hattie the Halfsie,” she said, giving us a little salute. “Which one of you is the famous feral?”

“Don’t call her that,” snapped a teenage boy with a huge, pulsating boil on his neck. “It’s derogatory.”

“Fine, uncontacted.”

“She’s not that either, anymore,” said Dogface. “She’s had to learn fast.”

The warthog girl let out a snorting laugh. “Not fast enough, from the looks of her!”

Noor’s jaw was locked tight, as if through sheer force of will she was forcing herself forward.

“These curious souls are the Untouchables,” Dogface said, turning to walk backward for a moment, like a tour guide. “The ones no other clan wanted.”

“Too peculiar to ever pass as normal,” said Hattie.

“The most appalling, most unspeakable, most disgusting peculiars anywhere!” the boy with the boil said proudly.

“I don’t think you’re disgusting,” said Bronwyn.

“Take it back!” said warthog girl, scowling.

Dogface twirled like a dancer and slid through an open door. “And this is our sanctum sanctorum. Well, the front door, anyhow.”

We followed him into the room, and then Noor and I stopped cold. In the middle of the floor was an operating table, and honeycombed into the back wall were a dozen small freezer doors. This room was not only a dead end, it was the hospital’s morgue.

“It’s okay,” Bronwyn said to Noor, gentle but urgent. “It won’t kill us.”

“Oh, hell no,” Noor said, backing away. “There’s no way I’m hiding in one of those things.”

“Not hiding,” Hugh said. “Traveling.”

“She don’t like it,” said the warthog girl. “She’s scared!”

The Untouchables all tittered in the doorway behind us.

Noor was already out of the room, crossing to another open door across the hall, the last alternative before going back the way we’d come.

Bronwyn and Hugh started after her, but I blocked them. “Let me talk to her,” I said.

Climbing into a morgue freezer would’ve been a hard sell for anyone, peculiar or otherwise, but especially for someone so new to this world. I didn’t particularly relish the idea myself.

I ran across the hall to join Noor in the other room. There was a bare metal cot lit by a beam of sunlight from a barred window. The corners were stacked up with discarded personal items that had belonged, presumably, to people who’d lived and died in the institution. Suitcases. Shoes.

Noor was agitated, turning from side to side. “I could’ve sworn I saw a door here. When we were running by before . . .”

“There’s no other way out,” I said.

Then I saw it, and my stomach sank.

“You mean this?”

She turned to look, and when she registered what it was, I thought she might cry. It was part of a mural on the wall. A trompe l’oeil; a door made of paint.

And then we heard the piano clang—once, twice, three times. Leo’s men had climbed through.

“We have a choice,” I said. “We can either . . .”

She wasn’t listening. She was focused on the barred window and the sun beaming through it.

I started again. “We can either stay here and wait for them to definitely find us . . .”

She swept the air with both hands but succeeded only in scraping finger-trails of darkness through it, which quickly filled in again with light. I’d seen this sort of thing before: Some peculiar abilities function like muscles, and they can be strained, exhausted. Others get shy when the pressure’s on.

She turned to face me. “Or I can trust you.”

“Yes,” I said, willing her toward me with every fiber of myself. “Me and a bunch of weirdos.”

Leo’s men were thundering down the outer hallway, searching rooms, rattling locked doors.

“This is absurd.” She shook her head, then met my eyes, and something in her steadied. “I shouldn’t trust you. But I do.”

She’d accepted so much absurdity already. What was a little more, in the balance, when it might save us?

Bronwyn and Hugh were waiting at the door, looking panicked. “Ready?” Hugh said.

“Better be,” said Dogface, leaning in. “By the way, if we have to cosh one of ’em for you, that’s a thousand.”

“Or Miss Poubelle can memory-wipe ’em for two,” said the boy with the pulsating boil.

The men spotted us darting across the hall. I didn’t look back, but I could hear their shouts and footfalls. The Untouchables had disappeared—they clearly didn’t want to tangle with Leo’s men, or make enemies of them, if they didn’t have to.

In the morgue, one of the lower body freezers was now unlatched and hanging open. Hugh was standing beside it—and when he saw us coming he called to us, waved us on, and dove in.

We ran to the open freezer and squinted into the blackness inside. It wasn’t just a cabinet for a corpse: it was a narrow tunnel that seemed to go on forever. Hugh’s voice echoed from somewhere deep within, receding quickly. “Whoooaaaaa!”

I waited for Noor to go first. “This is stupid I’m so stupid this is so so stupid,” she was chanting, but then she took a deep breath, steeled herself, and climbed in headfirst. She slid in partway but then got a little stuck, so I grabbed her feet and pushed, and in a moment the little compartment in the morgue wall swallowed her up.

Bronwyn went next, at my insistence, and then it was my turn. It was harder to make myself climb in than it should’ve been, considering I was the one who had convinced Noor to do it. It was such an unnatural action, shoving oneself into a morgue tray, that it took a few seconds of special effort for my rational mind—which knew that horrible, dark tunnely places made excellent loop entrances—to overcome my natural instincts, which were saying no, no, no, you’ll be eaten by zombies, nooooo. The sound of angry men bursting through the door behind me helped a great deal, though, and before they got to me I was in, wriggling deeper and deeper as fast as I could.

A hand grabbed my foot. I managed to kick it off. I heard a struggle behind me, and there was a dull thud and one of the men cried out. I glanced back to see one of Leo’s guys falling to the floor, the warthog girl behind him with a hunk of wood held in her hand.

I could hear Noor ahead of me, somewhere, grunting as she army-crawled forward on her elbows, farther and farther into the black. I pushed forward, then began to slide without effort. The tunnel was greased with something, and it angled downward slightly; after a few feet, forward momentum began to take me. It felt something like being born, I imagined, only faster and much longer—then I heard Noor scream. I felt myself being actively pulled through by something—not a hand but a bodiless force that gripped every part of me—like gravity. I felt that quickening in my blood and that lurch in my stomach that I knew so well.

We were crossing over.

We tumbled out of a small closet onto the long, red-carpeted hallway of Bentham’s Panloopticon. Bronwyn was collecting herself when Noor and I arrived, and Hugh was already waiting, looking slightly impatient.

“I was beginning to wonder if you’d decided not to join us!” he said as Bronwyn pulled Noor and I up effortlessly.

“Do you think they’ll come after us?” I said, glancing nervously at the door.

“No chance,” Bronwyn said. “The Untouchables like to get paid.”

I turned to Noor. “How are you?” I said, quiet and close.

“I’m fine,” she said quickly, seeming embarrassed. “Really sorry about my little freak-out back there.” She was talking to the three of us and looking around at the plush hallway. “This place is definitely better than the one we just left.”

Hugh started to say we should be going, but Noor interrupted him. “One more thing I need to say before we go anywhere or meet anyone else.” She looked at us. “Thank you all for helping me. I’m grateful.”

“You’re welcome,” Hugh said, maybe a bit too breezily.

She frowned. “I’m serious.”

“We are, too,” said Bronwyn.

“You can thank us when we get back to the house,” said Hugh. “Come on, or Sharon’s toadies will notice us and start asking questions I imagine we’d rather not answer.”

“Right enough,” Bronwyn said.

We walked quickly down the hall in a tight cluster. This section of the Panloopticon was relatively deserted, but after rounding a few corners, it began to get crowded. Peculiars dressed in outfits spanning every era and style were coming and going from loop doors. A sand drift was collecting outside one door, and a howling wind was spitting rain from another, held open a crack by a brick stuck in the jamb. People were lined up against the walls to have their travel documents checked and stamped by bureaucrats at small standing desks, and the echo of voices and footsteps and papers being shuffled made the place sound like a train station at evening rush hour.

Noor’s eyes were wide and roving, and I could hear Bronwyn, a hand on her back, attempting to explain our surroundings in a low voice.

“Every one of these doors leads to a different loop . . . It’s called the Panloopticon and it was invented by Miss Peregrine’s extremely brilliant brother Bentham . . . then taken over by her extremely evil other brother, and our worst enemy, Caul—”

“It’s actually proved quite useful,” Hugh cut in. “This loop we’re in, Devil’s Acre, used to be a prison for miscreant peculiars . . . then became a lawless place and our enemies, the wights, made their headquarters here—”

“Until Jacob helped us smash them and killed their leader,” Bronwyn said proudly.

At the mention of Caul, goose bumps had spontaneously broken out on my arms. “He’s not exactly dead,” I interjected.

“Fine,” said Hugh, “he’s trapped in a collapsed loop he can never, ever get out of, which is basically the same thing.”

“And now the wights are all dead or locked up in jail,” said Bronwyn. “And because they destroyed or seriously damaged many of our loops, a lot of peculiars had nowhere else to go and were forced to move in here.”

“Temporarily, we hope,” Hugh said. “The ymbrynes are trying to rebuild the loops we lost now.”

Noor was starting to look overwhelmed, so I said, “Maybe we should save the history lecture for later.”

We were passing a long row of windows, and Noor stared out as we walked. It was Devil’s Acre on a supersaturated-yellow afternoon, the kind only intense air pollution can create: the Acre’s crumbling buildings; snaking, green-black Fever Ditch; Smoking Street’s eternal haze; and beyond it, old London, a confusion of spires and gray buildings receding into a cauldron of Industrial Age soot.

“My God,” Noor said, voice just above a whisper.

I was walking next to her.

“This is London. Late nineteenth century. And you’re feeling that thing again, aren’t you?”

“The can’t-be-reals,” she said, slowing long enough to reach through an open window and wipe one finger along the ledge. As we sped up to keep pace with the others, she held it up. Her finger had turned black with soot. “But it is real,” she marveled.

“Yes, it is.”

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children Hollow City

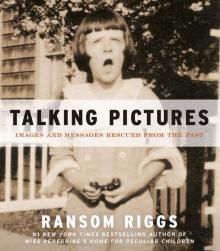

Hollow City Talking Pictures: Images and Messages Rescued From the Past

Talking Pictures: Images and Messages Rescued From the Past Tales of the Peculiar

Tales of the Peculiar The Desolations of Devil's Acre

The Desolations of Devil's Acre Library of Souls

Library of Souls A Map of Days

A Map of Days Hollow City: The Second Novel of Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children

Hollow City: The Second Novel of Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children Talking Pictures

Talking Pictures