- Home

- Ransom Riggs

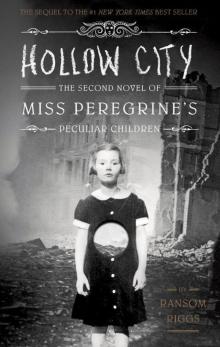

Hollow City: The Second Novel of Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children Page 3

Hollow City: The Second Novel of Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children Read online

Page 3

I’d never met anyone with Emma’s brash confidence. Everything about her exuded it: the way she carried herself, with shoulders thrown back; the hard set of her teeth when she made up her mind about something; the way she ended every sentence with a declarative period, never a question mark. It was infectious and I loved it, and I had to fight a sudden urge to kiss her, right there in front of everyone.

Hugh coughed, and bees tumbled out of his mouth to form a question mark that shivered in the air. “How can you be so bloody sure?” he asked.

“Because I am, that’s all.” And she brushed her hands as if that were that.

“You make a nice rousing speech,” said Millard, “and I hate to spoil it, but for all we know, Miss Peregrine is the only ymbryne left uncaptured. Recall what Miss Avocet told us: the wights have been raiding loops and abducting ymbrynes for weeks now. Which means that even if we could find a loop, there’d be no way of knowing whether it still had its ymbryne—or was occupied instead by our enemies. We can’t simply go knocking on loop doors and hoping they aren’t full of wights.”

“Or surrounded by half-starved hollows,” Enoch said.

“We won’t have to hope,” Emma said, then smiled in my direction. “Jacob will tell us.”

My entire body went cold. “Me?”

“You can sense hollows from a distance, can’t you?” said Emma. “In addition to seeing them?”

“When they’re close, it kind of feels like I’m going to puke,” I admitted.

“How close do they have to be?” asked Millard. “If it’s only a few meters, that still puts us within devouring range. We’d need you to sense them from much farther away.”

“I haven’t exactly tested it,” I said. “This is all so new to me.”

I’d only ever been exposed to Dr. Golan’s hollow, Malthus—the creature who’d killed my grandfather, then nearly drowned me in Cairnholm’s bog. How far away had he been when I’d first felt him stalking me, lurking outside my house in Englewood? It was impossible to know.

“Regardless, your talent can be developed,” said Millard. “Peculiarities are a bit like muscles—the more you exercise them, the bigger they grow.”

“This is madness!” Enoch said. “Are you all really so desperate that you’d stake everything on him? Why, he’s just a boy—a soft-bellied normal who knows next to nothing of our world!”

“He isn’t normal,” Emma said, grimacing as if this were the direst insult. “He’s one of us!”

“Stuff and rubbish!” yelled Enoch. “Just because there’s a dash of peculiar blood in his veins doesn’t make him my brother. And it certainly doesn’t make him my protector! We don’t know what he’s capable of—he probably wouldn’t know the difference between a hollow at fifty meters and gas pains!”

“He killed one of them, didn’t he?” said Bronwyn. “Stabbed it through the eyes with a pair of sheep shears! When’s the last time you heard of a peculiar so young doing anything like that?”

“Not since Abe,” Hugh said, and at the mention of his name a reverent hush fell over the children.

“I heard he once killed one with his bare hands,” said Bronwyn.

“I heard he killed one with a knitting needle and a length of twine,” said Horace. “In fact, I dreamed it, so I’m certain he did.”

“Half of those stories are just tall tales, and they get taller with every year that passes,” said Enoch. “The Abraham Portman I knew never did a single thing to help us.”

“He was a great peculiar!” said Bronwyn. “He fought bravely and killed scores of hollows for our cause!”

“And then he ran off and left us to hide in that house like refugees while he galavanted around America, playing hero!”

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” Emma said, flushing with anger. “There was a lot more to it than that.”

Enoch shrugged. “Anyway, that’s all beside the point,” he said. “Whatever you thought of Abe, this boy isn’t him.”

In that moment I hated Enoch, and yet I couldn’t blame him for his doubts about me. How could the others, so sure and seasoned in their abilities, put so much faith in mine—in something I was only beginning to understand and had known I was capable of for only a few days? Whose grandson I was seemed irrelevant. I simply didn’t know what I was doing.

“You’re right, I’m not my grandfather,” I said. “I’m just a kid from Florida. I probably got lucky when I killed that hollow.”

“Nonsense,” said Emma. “You’ll be every bit the hollow-slayer Abe was, one day.”

“One day soon, let’s hope,” said Hugh.

“It’s your destiny,” said Horace, and the way he said it made me think he knew something I didn’t.

“And even if it ain’t,” said Hugh, clapping his hand on my back, “you’re all we’ve got, mate.”

“If that’s true, bird help us all,” said Enoch.

My head was spinning. The weight of their expectations threatened to crush me. I stood, unsteady, and moved toward the cave exit. “I need some air,” I said, pushing past Enoch.

“Jacob, wait!” cried Emma. “The balloons!”

But they were long gone.

“Let him go,” Enoch grumbled. “If we’re lucky, he’ll swim back to America.”

* * *

Walking down to the water’s edge, I tried to picture myself the way my new friends saw me, or wanted to: not as Jacob, the kid who once broke his ankle running after an ice cream truck, or who reluctantly and at the behest of his dad tried and failed three times to get onto his school’s noncompetitive track team, but as Jacob, inspector of shadows, miraculous interpreter of squirmy gut feelings, seer and slayer of real and actual monsters—and all that might stand between life and death for our merry band of peculiars.

How could I ever live up to my grandfather’s legacy?

I climbed a stack of rocks at the water’s edge and stood there, hoping the steady breeze would dry my damp clothes, and in the dying light I watched the sea, a canvas of shifting grays, melded and darkening. In the distance a light glinted every so often. It was Cairnholm’s lighthouse, flashing its hello and last goodbye.

My mind drifted. I lapsed into a waking dream.

I see a man. He is of middle age, cloaked in excremental mud, crabbing slowly along the knife tip of a cliff, his thin hair uncombed and hanging wet across his face. Wind whips his thin jacket like a sail. He stops, drops to his elbows. Slips them into divots he’d made weeks before, when he was scouting these coves for mating terns and shearwaters’ nests. He raises a pair of binoculars to his eyes but aims them low, below the nests, at a thin crescent of beach where the swelling tide collects things and heaves them up: driftwood and seaweed, shards of smashed boats—and sometimes, the locals say, bodies.

The man is my father. He is looking for something that he desperately does not want to find.

He is looking for the body of his son.

I felt a touch on my shoe and opened my eyes, startled out of my half-dream. It was nearly dark, and I was sitting on the rocks with my knees drawn into my chest, and suddenly there was Emma, breeze tossing her hair, standing on the sand below me.

“How are you?” she asked.

It was a question that would’ve required some college-level math and about an hour of discussion to answer. I felt a hundred conflicting things, the great bulk of which canceled out to equal cold and tired and not particularly interested in talking. So I said, “I’m fine, just trying to dry off,” and flapped the front of my soggy sweater to demonstrate.

“I can help you with that.” She clambered up the stack of rocks and sat next to me. “Gimme an arm.”

I offered one up and Emma laid it across her knees. Cupping her hands over her mouth, she bent her head toward my wrist. Then, taking a deep breath, she exhaled slowly through her palms and an incredible, soothing heat bloomed along my forearm, just on the edge of painful.

“Is it too much?” she said.

> I tensed, a shudder going through me, and shook my head.

“Good.” She moved farther up my arm to exhale again. Another pulse of sweet warmth. Between breaths, she said, “I hope you’re not letting what Enoch said bother you. The rest of us believe in you, Jacob. Enoch can be a wrinkle-hearted old titmouse, especially when he’s feeling jealous.”

“I think he’s right,” I said.

“You don’t really. Do you?”

It all came pouring out. “I have no idea what I’m doing,” I said. “How can any of you depend on me? If I’m really peculiar then it’s just a little bit, I think. Like I’m a quarter peculiar and the rest of you guys are full-blooded.”

“It doesn’t work that way,” she said, laughing.

“But my grandfather was more peculiar than me. He had to be. He was so strong …”

“No, Jacob,” she said, narrowing her eyes at me. “It’s astounding. In so many ways, you’re just like him. You’re different, too, of course—you’re gentler and sweeter—but everything you’re saying … you sound like Abe, when he first came to stay with us.”

“I do?”

“Yes. He was confused, too. He’d never met another peculiar. He didn’t understand his power or how it worked or what he was capable of. Neither did we, to tell the truth. It’s very rare, what you can do. Very rare. But your grandfather learned.”

“How?” I asked. “Where?”

“In the war. He was part of a secret all-peculiar cell of the British army. Fought hollowgast and Germans at the same time. The sorts of things they did you don’t win medals for—but they were heroes to us, and none more than your grandfather. The sacrifices they made set the corrupted back decades and saved the lives of countless peculiars.”

And yet, I thought, he couldn’t save his own parents. How strangely tragic.

“And I can tell you this,” Emma went on. “You’re every bit as peculiar as he was—and as brave, too.”

“Ha. Now you’re just trying to make me feel better.”

“No,” she said, looking me in the eye. “I’m not. You’ll learn, Jacob. One day you’ll be an even greater hollow-slayer than he was.”

“Yeah, that’s what everyone keeps saying. How can you be so sure?”

“It’s something I feel very deeply,” she said. “You’re supposed to, I think. Just like you were supposed to come to Cairnholm.”

“I don’t believe in stuff like that. Fate. The stars. Destiny.”

“I didn’t say destiny.”

“Supposed to is the same thing,” I said. “Destiny is for people in books about magical swords. It’s a lot of crap. I’m here because my grandfather mumbled something about your island in the ten seconds before he died—and that’s it. It was an accident. I’m glad he did, but he was delirious. He could just as easily have rattled off a grocery list.”

“But he didn’t,” she said.

I sighed, exasperated. “And if we go off in search of loops, and you depend on me to save you from monsters and instead I get you all killed, is that destiny, too?”

She frowned, put my arm back in my lap. “I didn’t say destiny,” she said again. “What I believe is that when it comes to big things in life, there are no accidents. Everything happens for a reason. You’re here for a reason—and it’s not to fail and die.”

I didn’t have the heart to keep arguing. “Okay,” I said. “I don’t think you’re right—but I do hope you are.” I felt bad for snapping at her before, but I’d been cold and scared and feeling defensive. I had good moments and bad, terrified thoughts and confident ones—though my terror-to-confidence ratio was pretty dismal at present, like three-to-one, and in the terrified moments it felt like I was being pushed into a role I hadn’t asked for; volunteered for front-line duty in a war, the full scope of which none of us yet knew. “Destiny” sounded like an obligation, and if I was to be thrust into battle against a legion of nightmare creatures, that had to be my choice.

Though in a sense the choice had been made already, when I agreed to sail into the unknown with these peculiar children. And it wasn’t true, if I really searched the dusty corners of myself, that I hadn’t asked for this. Really, I’d been dreaming of such adventures since I was small. Back then I’d believed in destiny, and believed in it absolutely, with every strand and fiber of my little kid heart. I’d felt it like an itch in my chest while listening to my grandfather’s extraordinary stories. One day that will be me. What felt like obligation now had been a promise back then—that one day I would escape my little town and live an extraordinary life, as he had done; and that one day, like Grandpa Portman, I would do something that mattered. He used to say to me: “You’re going to be a great man, Yakob. A very great man.”

“Like you?” I would ask him.

“Better,” he’d reply.

I’d believed him then, and I still wanted to. But the more I learned about him, the longer his shadow became, and the more impossible it seemed that I could ever matter the way he had. That maybe it would be suicidal even to try. And when I imagined myself trying, thoughts of my father crept in—my poor about-to-be-devastated father—and before I could push them out of my mind, I wondered how a great man could do something so terrible to someone who loved him.

I began to shiver. “You’re cold,” Emma said. “Let me finish what I started.” She picked up my other arm and kissed with her breath the whole length of it. It was almost more than I could handle. When she reached my shoulder, instead of placing the arm in my lap, she hung it around her neck. I lifted my other arm to join it, and she put her arms around me, too, and our foreheads nodded together.

Speaking very quietly, Emma said, “I hope you don’t regret the choice you made. I’m so glad you’re here with us. I don’t know what I’d do if you left. I fear I wouldn’t be all right at all.”

I thought about going back. For a moment I really tried to play it out in my head, how it would be if I could somehow row one of our boats back to the island again, and go back home.

But I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t imagine.

I whispered: “How could I?”

“When Miss Peregrine turns human again, she’ll be able to send you back. If you want to go.”

My question hadn’t been about logistics. I had meant, simply: How could I leave you? But those words were unsayable, couldn’t find their way past my lips. So I held them inside, and instead I kissed her.

This time it was Emma whose breath caught short. Her hands rose to my cheeks but stopped just shy of making contact. Heat radiated from them in waves.

“Touch me,” I said.

“I don’t want to burn you,” she said, but a sudden shower of sparks inside my chest said I don’t care, so I took her fingers and raked them along my cheek, and both of us gasped. It was hot but I didn’t pull away. Dared not, for fear she’d stop touching me. And then our lips met again and we were kissing again, and her extraordinary warmth surged through me.

My eyes fell closed. The world faded away.

If my body was cold in the night mist, I didn’t feel it. If the sea roared in my ears, I didn’t hear it. If the rock I sat on was sharp and jagged, I hardly noticed. Everything outside the two of us was a distraction.

And then a great crash echoed in the dark, but I thought nothing of it—could not take myself away from Emma—until the sound doubled and was joined by an awful shriek of metal, and a blinding light swept over us, and finally I couldn’t shut it out anymore.

The lighthouse, I thought. The lighthouse is falling into the sea. But the lighthouse was a pinpoint in the distance, not a sun-bright flash, and its light only traveled in one direction, not back and forth, searching.

It wasn’t a lighthouse at all. It was a searchlight—and it was coming from the water close to shore.

It was the searchlight of a submarine.

* * *

Brief second of terror in which brain and legs were disconnected. My eyes and ears registered the submarine not

far from shore: metal beast rising from the sea, water rushing from its sides, men bursting onto its deck from open hatches, shouting, training cannons of light at us. And then the stimulus reached my legs and we slid, fell, and pitched ourselves down from the rocks and ran like hell.

The spotlight threw our pistoning shadows across the beach, ten feet tall and freakish. Bullets pocked the sand and buzzed the air.

A voice boomed from a loudspeaker. “STOP! DO NOT RUN!”

We burst into the cave—They’re coming, they’re here, get up, get up—but the children had heard the commotion and were already on their feet—all but Bronwyn, who had so exhausted herself at sea that she had fallen asleep against the cave wall and couldn’t be roused. We shook her and shouted in her face, but she only moaned and brushed us away with a sweep of her arm. Finally we had to hoist her up by the waist, which was like lifting a tower of bricks, but once her feet touched the ground, her red-rimmed eyelids split open and she took her own weight.

We grabbed up our things, thankful now that they were so small and so few. Emma scooped Miss Peregrine into her arms. We tore outside. As we ran into the dunes, I saw behind us a gang of silhouetted men splashing the last few feet to shore. In their hands, held above their heads to keep them dry, were guns.

We sprinted through a stand of windblown trees and into the trackless forest. Darkness enveloped us. What moon wasn’t already hidden behind clouds was blotted out now by trees, branches filtering its pale light to nil. There was no time for our eyes to adjust or to feel our way carefully or to do anything other than run in a gasping, stumbling herd with arms outstretched, dodging trunks that seemed to coalesce suddenly in the air just inches from us.

After a few minutes we stopped, chests heaving, to listen. The voices were still behind us, only now they were joined by another sound: dogs barking.

We ran on.

We tumbled through the black woods for what seemed like hours, no moon or movement of stars by which to judge the passing time. The sound of men shouting and dogs barking wheeled around us as we ran, menacing us from everywhere and nowhere. To throw the dogs off our scent, we waded into an icy stream and followed it until our feet went numb, and when we crossed out of it again, it felt like I was stumbling along on prickling stumps.

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children Hollow City

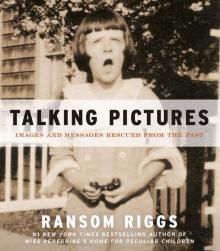

Hollow City Talking Pictures: Images and Messages Rescued From the Past

Talking Pictures: Images and Messages Rescued From the Past Tales of the Peculiar

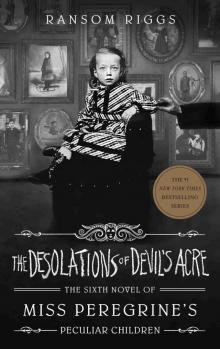

Tales of the Peculiar The Desolations of Devil's Acre

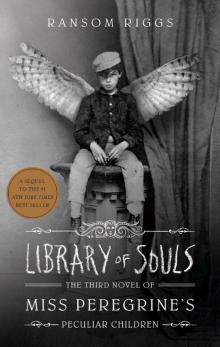

The Desolations of Devil's Acre Library of Souls

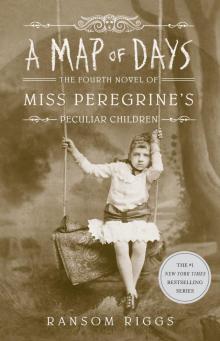

Library of Souls A Map of Days

A Map of Days Hollow City: The Second Novel of Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children

Hollow City: The Second Novel of Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children Talking Pictures

Talking Pictures