- Home

- Ransom Riggs

The Conference of the Birds Page 2

The Conference of the Birds Read online

Page 2

“If we fight, they start shooting, and I can’t let you get shot. I’ll give myself up and tell them you ran somewhere else—”

She was shaking her head vehemently. “No way in hell.” Even in the dark I could see her eyes flashing. She let the tiny ball of light she’d raked up dissipate and retrieved two long shards of glass from the floor. “We fight together or not at all.”

I let out a frustrated sigh. “Then we fight.” We crouched down, shards of glass held out like knives. The footsteps were loud, and so close we could hear the approaching runners’ heavy breaths.

And then they were here.

A figure appeared at the end of the hall, silhouetted against neon. Someone stocky, broad-shouldered . . . and familiar, though I couldn’t immediately place them.

“Mr. Jacob?” a voice I recognized said. “Is that you?”

A shimmer of light fell across her face. Her strong, square jaw, her kind eyes. I thought, for a moment, that I must be dreaming.

“Bronwyn?” I said—almost shouted.

“It is you!” she cried, her face breaking into a wide grin. She ran toward me, bounding around drifts of broken glass, and I dropped the shard of glass just before Bronwyn wrapped me in a big, breath-stealing hug. “Is that Miss Noor?” she said over my shoulder.

“Hi,” Noor said, sounding a bit stunned.

“Then you succeeded!” Bronwyn said. “I’m so happy!”

“What are you doing here?” I managed to squeak.

“We might ask the same of you!” said another familiar voice—and as Bronwyn let me go I saw Hugh coming toward us. “Blimey, what happened in here?”

First Bronwyn, now Hugh. My head was spinning.

Bronwyn set me down. “Never mind that. He’s all right, Hugh! And here’s Miss Noor.”

“Hi,” Noor said again. Then, quickly, “So there’s, like, four guys with guns coming for us right now—”

“I coshed two on the head,” said Bronwyn, holding up a pair of fingers.

“I chased off another with my bees,” said Hugh.

“More will be coming,” I said.

Bronwyn picked up a heavy-looking metal bar from the floor. “Then let’s not dally, shall we?”

* * *

◆ ◆ ◆

The subterranean seafood market was a baffling maze, but we navigated its wriggling nooks and crannies as best we could, each twosome struggling to remember just how we’d gotten down here and which of the Chinese-language signs around us meant exit. The place was both cramped and sprawling, packed tight with crates and tables, divided by hanging tarps, nests of dangerous-looking electric wires and bare bulbs that swung overhead. It had been crowded a short time ago, but Leo’s guys had pretty well cleared it out.

“Try and keep up!” Bronwyn called over her shoulder.

We slid after her under a table squirming with live octopi, then chased her down an aisle of fish laid out in boxes of steaming dry ice. Turning left at a junction with another aisle, we saw two of Leo’s men—one was splayed on the ground, and the other was crouching next to him, attempting to revive him with little slaps on the face. Bronwyn didn’t slow her pace at all, and the man looked up in surprise just as she delivered a running kick to his head and sent him sprawling onto the ground beside the other one.

“Very sorry!” she called behind her, and in reply there came a pair of shouts from far across the market—two more of Leo’s guys had spotted us and were now charging in our direction. We took a sharp turn and ran up a narrow stairway, then slammed through a door and burst out into daylight, briefly blinded after having spent so long in the gloom. Suddenly, we were on a busy sidewalk at rush hour in the present day. Cars and pedestrians and street vendors were everywhere, zipping around us in a dizzying whirl.

There’s an art to fleeing casually. It’s not easy, running from something that might kill you while not attracting stares. Seeming to be engaged in something no more dramatic than an afternoon jog, especially when two of you are soaked head to toe, two of you are dressed in nineteenth-century clothes, and all of you keep shooting nervous glances down every alley and back over your shoulders. Apparently, we hadn’t got the hang of it, because we were getting even more stares than two costumed and two wet teenagers should have warranted, especially in New York, where strange people populated most sidewalks.

We jaywalked, we ignored red lights and DON’T WALK signs, edging into the street until there was a stall in traffic, or sometimes just going for it in a mad dash and letting the cars honk and swerve, because getting run over was better than being dragged back to Leo’s loop. His goons had been on us like a bad cold, tailing us through the grit of Chinatown and up the streets of a touristy Italian neighborhood, then nearly catching up to us when we got stuck on the median strip of busy Houston Street. They were easy to spot in their old suits. Finally, just when I was beginning to wonder how much longer I could run, Noor poured on more speed to catch up with Bronwyn and pulled her around a corner. Hugh and I followed them, and a short time later Noor hauled Bronwyn to the side again, this time through a door into a seemingly random store. It was a cramped little bodega that sold beer and dry goods.

As the owner shouted something at us, we all saw two of Leo’s guys dash past the front door without stopping. Then Noor pushed us down a narrow aisle, through a door into a stockroom, past a surprised employee on a smoke break, and out through a swinging metal door into an alley lined with dumpsters.

It seemed we had shaken them off—for a moment, anyway—and we allowed ourselves to stop for a minute and catch our breath. Bronwyn had hardly broken a sweat, but Noor, Hugh, and I were gasping.

“That was quick thinking,” Bronwyn said, impressed.

“Yeah,” Hugh said. “Nicely done.”

“Thanks,” said Noor. “Not my first rodeo.”

“We should be safe here for a minute,” Hugh said between breaths. “Let’s give them some time to think we’re long gone, then move.”

“I should probably ask where you’re taking us,” I said.

“I’d certainly love to know,” Noor said, one eyebrow rising.

“Back to the Acre,” said Hugh. “Closest loop entrance ain’t pleasant, but it ain’t far . . .”

I couldn’t stop looking at my friends. Part of me had worried I might never lay eyes on them again. Or that, if I did, they would act like strangers.

And then Hugh drew back his fist and punched me in the arm.

“Ow! What was that for?”

“Why didn’t you tell us you were doing some daft rescue mission?”

Noor was gaping at us.

“I tried,” I said.

“Not very hard, you didn’t!” said Bronwyn.

“Well, I dropped some awfully big hints,” I said defensively. “But it was pretty clear no one wanted to help me.”

Hugh looked ready to punch me again. “Maybe not, but we would have!”

“We never would have let you do something like this alone,” Bronwyn said, sounding angry at me for the first time. “We were worried sick when we found you gone!” She turned to Noor and shook her head. “He was in a sickbed just yesterday, mad boy. Thought somebody’d kidnapped him in the night!”

“To be honest, I wasn’t really sure you’d care that I was gone,” I said.

“Jacob!” Bronwyn’s eyes went wide. “After all we’ve been through? That’s just hurtful.”

“Told you he was a Sensitive Sally.” Hugh shook his head. “Give your old mates some credit, man. My God.”

“Sorry,” I said meekly.

“I mean, really.”

Noor leaned toward me and whispered, “No friends, huh?”

“I don’t know what to say.” My heart was suddenly so full it seemed to crowd out the words from my brain. “I’m really glad to see you guys.”

“And we you,” said Bronwyn. She hugged me again, and this time Hugh did, too.

And then a gunshot rang out from one end of the alley and we all startled, then broke apart to see two men in suits booking it toward us.

So much for shaking them off.

“Follow me,” Noor said. “We can lose them in the subway.”

* * *

◆ ◆ ◆

I shot down the subway steps three at a time. Hugh slid on the metal banister. In the crowded vestibule we shoved through knots of rush-hour commuters. Noor shouted, “Like this!” behind her and then jumped a turnstile—we all followed suit.

We came to a train platform and ran along it. I looked back and saw Leo’s guys, distant but still chasing us. Noor stopped, planted a hand on the floor, jumped down onto the subway tracks, and shouted for us to follow. She yelled something about a third rail, too, though her voice got lost in the noise of a sudden station announcement.

We had no choice but to go after her.

“You’re gonna get yourselves killed!” somebody yelled at us, and I was inclined to agree—but right now this seemed preferable to the alternative.

We were dashing across four sets of tracks, stumbling over hidden pits and dark rails, when it occurred to me that Noor had obviously done this before, that she knew the city like the back of her hand, and that someone so hard to catch must have had lots of experience running away. And I wondered why and from what, and I very much hoped, as I noticed a train coming, that I’d get a chance to ask her.

The train was uncomfortably close as Hugh and I crossed the last track, the wind and noise it pushed strengthening by the second, and then Bronwyn and Noor hauled us up onto the opposite platform just before it thundered past, brakes squealing like some creature from hell.

Moments later the train disgorged its passengers, and suddenly there seemed to be a thousand people on the platform, but finally we were able to push our way on board. We crouched down on the floor so we couldn’t be seen—the car was nearly empty—and then the doors slid shut.

“Gee,” Bronwyn said, looking suddenly worried. “I hope this train’s going in the right direction . . .”

Noor asked where we were supposed to be heading, and Bronwyn told her. Noor raised her eyebrows. “Weird luck,” she said. “That’s just a stop away.”

It was amazing: Of the four of us, she knew by far the least about what was happening, but her certainty and calm had already become a guiding force.

An announcement blared and the train took off from the station.

“How did you find me?” I said to Bronwyn and Hugh.

“Emma realized what you were probably up to, after all your talk about her.” Hugh nodded to Noor and said, “Nice to properly meet you, by the way, I’m Hugh . . .” He reached over and shook Noor’s hand.

“It was a fairly simple matter to find you after that,” Bronwyn said. “Oh, and we had some help from a dog. Remember Addison?”

I nodded.

“Sharon’s Panloopticon toadies tracked you to New York, and Addison’s nose was able to track you to that market,” said Hugh. “But that’s as far as he would go.”

Bless that little dog, I thought. I was losing count of how many times he’d risked his life for us.

“You were easy to find from there,” said Bronwyn. “We followed the shouting.”

“Did Miss Peregrine send you?” I said.

“No,” said Hugh. “She doesn’t know about this.”

“She probably does by now,” said Bronwyn. “She’s awfully good at knowing things.”

“We thought more than two of us leaving might attract too much attention.”

“We all drew straws,” said Bronwyn. “Hugh and me won.” She glanced at Hugh. “Think Miss P will be mad at us for coming?”

Hugh nodded vigorously. “Steaming. But proud, too. Assuming we can get him back home in one piece.”

“Home?” Noor said. “Where’s that?”

“A loop in late-1800s London called Devil’s Acre,” Hugh said. “Closest thing we got to a home, anyhow.”

Noor’s eyebrows furrowed. “Sounds . . . delightful.”

“It’s rough around the edges, but it has a certain charm. It’s better than living out of a suitcase, at any rate.”

Noor looked a bit doubtful. “And it’s a place for people like you?”

“For people like us,” I said.

She didn’t react, or tried not to, but I saw a flicker of something behind her eyes. An idea, perhaps, that was starting to register. Us.

“You’ll be safe there,” said Bronwyn. “No men with guns chasing you . . . no helicopters . . .”

I was about to agree, but then I remembered H’s warning about the ymbrynes, and the things Miss Peregrine had said to me in the last conversation we’d had, about certain sacrifices being necessary for the greater good. One of those sacrifices being Noor herself.

“What about all the things H told us we need to do?” Noor said to me.

She had lowered her voice a bit, unsure of whether Bronwyn and Hugh knew, or should know, about this.

“All what things?” Hugh asked.

I said, “Before he died, H gave me some information about Noor and the people who’ve been chasing her, and he said we needed to find a woman named V. That there were important things about this that only she knew.”

“V? Isn’t that the hollow-slayer your grandfather trained?” asked Bronwyn.

Bronwyn had been at the diviners’ loop when V’s name had first come up. Of course she remembered.

“The same,” I said. “And H—well, his hollowgast—showed us a map and gave us some instructions on how to find her—”

“His hollowgast?” gasped Bronwyn.

I pulled the paper map fragment out of my pocket and showed them. “He wasn’t a hollowgast anymore. He was turning into something else.”

“You mean a wight?” said Hugh. “That’s the only thing hollows turn into.”

Noor gave me a confused look. “You said the wights are our enemies.”

“They are,” I said. “But H was friends with this particular hollow . . .”

“This is getting more and more surreal,” Noor said.

“I know. And that’s why I think we should go with them to Devil’s Acre,” I said. “We need help, and all the peculiars I know and trust are there.”

Whether or not they would ever trust me again, or would be willing to help after what I’d put them through, was another matter. But I had to try. I needed my friends, H’s warning be damned.

If Miss Peregrine was really capable of sending the girl we had just helped rescue back into the hands of her captors for some political reason—or any reason—then she wasn’t the Miss Peregrine I thought I knew. And if I couldn’t keep Noor from harm in a loop full of friends, how was I supposed to help her navigate the wilderness of peculiar America?

“Millard’s a cartography expert,” said Bronwyn.

“And Horace is a prophet,” I added. “Part-time, at least.”

“Yeah,” Noor said, her eyes sliding to me. “You never finished telling me about that.”

The prophecy. I wanted to tell her in private, not in front of other people. It seemed we were no longer in immediate danger.

“It can wait,” I said.

Hugh and Bronwyn both gave me curious looks.

“If you say so,” Noor said, but she was starting to sound impatient.

The train began to stop. We were at the next station.

* * *

◆ ◆ ◆

We ran up out of the subway and back onto daylit streets. Noor took a moment to help Bronwyn get oriented.

“It’s not far now,” Bronwyn promised, guiding us diagonally through four lanes of traffic as horns blared.

We cut through a basketball court with a game in progress, through a sad green space overwhelmed by a looming pair of old condo towers. With each block the neighborhood was getting worse, rusty and chewed-up, until finally we were in the shadow of a huge brick building covered in scaffolding and ringed by chain-link fences skinned with green tarps. Bronwyn stopped and pulled a tarp back, revealing a hole in the fence. Noor and I traded a quick, hesitant glance.

Bronwyn and Hugh waved at us to follow and then disappeared through the hole.

Hugh popped his head back out. “You two coming?”

Noor squeezed her eyes shut for a second—no doubt fighting some version of What the hell am I doing? in her head—then climbed through. Though she might not have believed me, I often fought that same battle. A voice inside me had been shouting What the hell are you doing? more or less daily since I’d gone to Wales on a hunch to chase down ghosts from old photos. I’d gotten better at tuning it out, and it had gotten a lot quieter. But it was still there.

On the other side of the fence was a different world—or a much sadder and grimmer one, at any rate. Stepping through was like peeling back a corpse’s shroud. The building had been built and finished long ago, then left to ruin. I stood in the wild grass and allowed myself one long breath to take it in—ten stories tall and wide as a city block, leaded windows all broken, bricks scabbed and veined with dead vines. Grand steps led up to a doorway framed in fancy wrought-iron curlicues. Above it, carved into a heavy marble slab, were the words PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITAL.

“How fitting,” Noor said under her breath. “I must be losing my mind.”

“You’re not.” I’d been waiting for this: for everything to start sinking in. “I know it feels like you are, but you’re not, I promise.”

Bronwyn and Hugh were twenty feet ahead, waving with increasing urgency for us to follow.

Noor wasn’t looking at me. “I was drugged. I ate bad mushrooms. I’m in a coma. This is all a dream.” She rubbed her hands on her face. “Anything makes more sense than—”

I said, “I can’t prove you’re not dreaming. But I do know what you’re going through.”

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children Hollow City

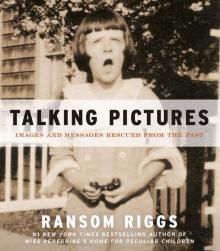

Hollow City Talking Pictures: Images and Messages Rescued From the Past

Talking Pictures: Images and Messages Rescued From the Past Tales of the Peculiar

Tales of the Peculiar The Desolations of Devil's Acre

The Desolations of Devil's Acre Library of Souls

Library of Souls A Map of Days

A Map of Days Hollow City: The Second Novel of Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children

Hollow City: The Second Novel of Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children Talking Pictures

Talking Pictures