- Home

- Ransom Riggs

Library of Souls Page 10

Library of Souls Read online

Page 10

“We’ve all got demons to slay,” I said.

I leaned against a boarded window, a sudden wave of exhaustion breaking over me. How long had we been awake? How many hours since Caul had revealed himself? It seemed like days ago, though it couldn’t have been more than ten or twelve hours. Every moment since had been a war, a nightmare of struggle and terror without end. I could feel my body inching toward collapse. Panic was the only thing keeping me upright, and whenever it began to fade, I did, too.

For the merest fraction of a second, I allowed my eyes to close. Even in that slim black parenthesis, horrors awaited me. A specter of eternal death, crouched and feeding upon the body of my grandfather, its eyes weeping oil. Those same eyes planted with the twin stalks of garden shears, howling as it sank into a boggy grave. Its master’s face contorted in pain, tumbling backward into a void, gutshot, screaming. I had slain my demons already, but the victories were fleeting; others had risen up quickly to replace them.

My eyes flew open at the sound of footsteps behind me, on the other side of the boarded-up window. I hopped away and turned. Though the store looked abandoned, someone was inside, and they were coming out.

There it was: panic. I was awake again. The others had heard the noise, too. Acting on collective instinct, we ducked behind a stack of firewood nearby. Through the logs I peeked at the storefront, reading the faded sign that hung above the door.

Munday, Dyson and Strype, attnys at law. Hated and feared since 1666.

A bolt slid and slowly the door opened. A familiar black hood appeared: Sharon. He looked around, judged the coast clear, then slipped out and locked the door behind him. As he hurried away in the direction of Louche Lane, we consulted in whispers about whether to go after him. Did we need him anymore? Could he be trusted? Maybe and maybe. What had he been doing in that shuttered storefront? Was this the lawyer he’d talked about seeing? Why the sneaking?

Too many questions, too many uncertainties about him. We decided we could make it on our own. We stayed put and watched as he turned ghostly in the murk and was gone.

* * *

We set out to find Smoking Street and the wights’ bridge. Not wanting to risk another unpredictable encounter, we resolved to search without asking for directions. That became easier once we discovered the Acre’s street signs, which were concealed in the most inconvenient places—behind public benches at knee height, dangling from the tops of lampposts, inscribed into worn cobblestones underfoot—but even with their help, we took as many wrong turns as right. It seemed the Acre had been designed to drive those trapped inside it mad. There were streets that ended at blank walls only to begin again elsewhere. Streets that curved so sharply they spiraled back on themselves. Streets with no name—or two or three. None were as tidy or tended to as Louche Lane, where it was clear a special effort had been made to create a pleasing environment for shoppers in the market for peculiar flesh—the idea of which, now that I’d seen Lorraine’s wares and heard Emma’s story, turned my stomach.

As we wandered, I began to get a handle on the Acre’s unique geography, learning the blocks less by their names than by their character. Each street was distinct, the shops along them grouped according to type. Doleful Street boasted two undertakers, a medium, a carpenter who worked exclusively with “repurposed coffinwood,” a troupe of professional funeral-wailers who did weekend duty as a barbershop quartet, and a tax accountant. Oozing Street was oddly cheerful, with flower boxes hanging from windowsills and houses painted bright colors; even the slaughterhouse that anchored it was an inviting robin’s-egg blue, and I resisted an odd impulse to go inside and ask for a tour. Periwinkle Street, on the other hand, was a cesspit. There was an open sewer running down its center, a thriving population of aggressive flies, and sidewalks that overflowed with putrefying vegetables, the property of a cut-rate greengrocer whose sign claimed he could turn them fresh again with a kiss.

Attenuated Avenue was just fifty feet long and had only one business: two men selling snacks from a basket on a sled. Children crowded around, clamoring for handouts, and Addison veered off to snuffle around their feet for droppings. I was about to call after him when one of the men shouted, “Cat’s meat! Boiled cat’s meat here!” He came scurrying back on his own, tail tucked between his legs, whimpering, “I shall never eat again, never, never again …”

We approached Smoking Street from Upper Smudge. The closer we got, the more the block seemed to wither, its storefronts abandoned, its sidewalks emptying, the pavement blackening with currents of ash that blew around our feet, as if the street itself had been infected by some creeping death. At the end it curved sharply to the right, and just before the bend was an old wooden house with an equally old man guarding its stoop. He swept at the ash with a stubbly broom, but it piled up faster than he could ever hope to collect it.

I asked him why he bothered. He looked up suddenly, hugging the broom to his chest as if afraid I’d steal it. His feet were bare and black and his pants were sooty to the knee. “Someone’s got to,” he said. “Can’t let the place go to hell.”

As we passed he returned grimly to his task, though his arthritic hands could hardly close around the stick. There was something almost regal about him, I thought; a defiance I admired. He was a holdout who refused to give up his post. The last watchman at the end of the world.

Turning with the road, we moved through a zone of buildings that shed their skins as we walked: first the paint was singed away, and farther along the windows had blackened and burst; next, the roofs were caving and the walls coming down, and finally, as we came to the junction with Smoking Street, only their bones were left—a chaos of timbers charred and leaning, embers glowing in the ash like tiny hearts beating their last. We stood and looked around, thunderstruck. Sulfurous smoke rose from deep cracks that fissured the pavement. Fire-stripped trees loomed like scarecrows over the ruins. Drifts of ash flowed down the street, a foot deep in places. It was as close to Hell as I ever intend to find myself.

“So this is the wights’ front driveway,” said Addison. “How fitting.”

“It’s unreal,” I said, unbuttoning my coat. Sauna-like warmth rose all around, radiating through the soles of my shoes. “What did Sharon say happened here?”

“Underground fire,” Emma said. “They can burn for years. Notoriously difficult to extinguish.”

There was a sound like a giant can of soda being opened, and a tall prong of orange flame shot up from a seam in the pavement not ten feet away. We started and jumped and then had to collect ourselves.

“Let’s not spend one minute longer here than we need to,” said Emma. “Which way?”

There was only left and right to choose from. We knew that Smoking Street terminated at the Ditch on one end and at the wights’ bridge on the other, but we didn’t know which way was which, and between the smoke, the fog, and the wind-blown ash, we couldn’t see far in either direction. Choosing at random could mean a dangerous detour and a waste of time.

We were getting desperate when we heard a warbling tune drifting toward us through the fog. We scuttled off the road to hide among the carbonized ribs of a house. As the singers approached, their voices growing louder, we could make out the words to their strange song:

The night before the thief was stretched,

the hangman came around

I’ve come, he said, before you’re dead,

a warning to expound

I’ll strangle your neck and send you to heck

and cut off your arm and do you some harm

and flay your hide and give you a riiiiiiiiide …

Here they all paused for breath, then finished with: “SIX FEET UNDER THE GROUND!”

Long before they emerged from the fog, I knew whose voices they were. The figures took form in black overalls and sturdy black boots, tool bags swinging gaily at their sides. Even after a hard day’s work, the indomitable gallows riggers were still singing at the top of their lungs.

“Bl

ess their tuneless souls,” Emma said, laughing softly.

Earlier we’d seen them working at the Ditch end of Smoking Street, so it seemed reasonable to assume that’s where they were coming from—which meant they were walking in the direction of the bridge. We waited for the men to pass and disappear again into the fog before venturing back onto the road to follow.

We shuffled through reefs of ash that blackened everything—the cuffs of my pants, Emma’s shoes and bare ankles, the full height of Addison’s legs. Somewhere in the distance the riggers took up another song, their voices echoing weirdly through the burned landscape. Nothing around us but ruin. Now and then we heard a sharp whoosh, quickly followed by a spout of flame bursting from the ground. None erupted as close as the first one. We were lucky—getting roasted alive here would’ve been easy.

Out of nowhere a wind kicked up, sending ash and hot cinders skyward in a black blizzard. We turned and covered our faces in an effort to breathe. I pulled my shirt collar over my mouth, but it didn’t help much and I started to cough. Emma took Addison into her arms, but then she started to choke. I tore off my coat and threw it over their heads. Emma’s coughing quieted and I heard Addison’s muffled voice say “Thank you!” beneath the fabric.

It was all we could do to huddle there and wait for the ash storm to end. I had my eyes closed when I heard something move nearby, and peeking through slit fingers I saw something that even here, amidst all I’d witnessed in Devil’s Acre, startled me: a man strolling casual as could be, a handkerchief pressed to his mouth but otherwise unperturbed. He had no trouble navigating the dark because beams of strong white light were shooting from each of his eye sockets.

“Evening!” he called out, swinging his sight-beams toward me and tipping his hat. I tried to reply but my mouth filled with ash and then so did my eyes, and when I reopened them he was gone.

As the wind began to die, we coughed and spat and rubbed our eyes until we could function again. Emma set Addison on the ground. “If we’re not careful, this loop will kill us before the wights do,” he said. Emma handed me back my coat and hugged me hard until the air cleared. She had a way of wrapping her arms around me and nudging her head into the hollow of my chest so that no gaps were left between us, and I wanted badly to kiss her, even here, covered in soot from head to toe.

Addison cleared his throat. “I hate to interrupt, but we really should be getting on.”

We unhooked our limbs, slightly embarrassed, and continued walking. Soon pale figures appeared in the fog ahead. They were milling in the street, crossing between shacks that encrusted the roadside. We hesitated, nervous about who they might be, but there was no other way forward.

“Chin up, back straight,” Emma said. “Try to look scary.”

We closed ranks and walked into their midst. They were shifty eyed and wild looking. Soot-stained all over. Dressed in scavenged castoffs. I scowled, doing my best impression of a dangerous person. They shied away like beaten dogs.

Here was a kind of shantytown. Low-slung huts made from fire-proof scrap metal, tin roofs weighed down with boulders and tree stumps, canvas flaps for doors if they had doors at all. A fungal smear of life overgrowing the bones of a burned civilization; hardly there at all.

Chickens ran in the street. A man knelt by a smoking hole in the road, cooking eggs in its blistering heat.

“Don’t get too close,” Addison muttered. “They look ill.”

I thought so, too. It was the limping way they carried themselves, their glassy stares. Several wore crude masks or sacks over their heads with only slits for eyes, as if to hide faces chewed by disease, or to slow a disease’s transmission.

“Who are they?” I asked.

“No idea,” said Emma, “and I’m not about to ask.”

“My guess is they’re welcome nowhere else,” Addison said. “Untouchables, plague carriers, criminals whose offenses are considered unforgivable even in Devil’s Acre. Those who escaped the noose settled here, at the very bottom, the absolute edge of peculiar society. Exiled from the outcasts of outcasts.”

“If this is the edge,” said Emma, “then the wights can’t be far away.”

“Are we sure these people are peculiar?” I asked. There seemed to be nothing unique about them, aside from their wretchedness. Maybe it was pride, but I didn’t believe a community of peculiars, however degraded, would allow themselves to live in such medieval squalor.

“Don’t know, don’t care,” Emma replied. “Just walk.”

We kept our heads down and our eyes forward, feigning disinterest in hopes that these people would return the favor. Most stayed away, but a few trailed us, begging.

“Anything, anything. A dropper, a vial,” said one, gesturing to his eyes.

“Please,” implored another. “We haven’t had a kick in days.”

Their cheeks were pocked and scarred, like they’d been crying tears of acid. I could hardly look at them.

“Whatever you want, we haven’t got it,” said Emma, shooing them away.

The beggars dropped back and stood in the road, watching us darkly. Another called out in a high, fraying voice. “You there! Boy!”

“Ignore him,” Emma muttered.

I side-eyed him without turning my head. He was squatting against a wall, in rags, pointing at me with a trembling hand.

“You him? Boy! You’re him, aincha?” He wore an eyepatch over glasses and flipped it up to study me. “Yeahhhhh.” He whistled low, then flashed a black-gummed smile. “They been waitin’ for you.”

“Who has?”

I couldn’t take it anymore. I stopped in front of him. Emma sighed impatiently.

The beggar’s smile grew wider, crazier. “The dust-mothers and knot-blowers! The damned librarians and blessed cartographers! Anyone who’s everyone!” He raised his arms and bowed in mocking worship, and I got a whiff of ripe funk. “Waitin’ a lonnnnnng time.”

“For what?”

“Come on,” said Emma, “he’s obviously a lunatic.”

“The big show, the big show,” said the beggar, his voice rising and falling like a carnival barker’s. “The biggest and best and most and last! It’s allllllllmost here …”

A weird chill rattled through me. “I don’t know you, and you sure as hell don’t know me.” I turned and walked away.

“Sure I do,” I heard him say. “You’re the boy who talks to hollows.”

I froze. Emma and Addison turned to gape at me.

I ran back, confronting him. “Who are you?” I shouted in his face. “Who told you that?”

But he just laughed and laughed, and I could get nothing more out of him.

* * *

We slipped away just as a crowd began to gather.

“Don’t look back,” Addison warned.

“Forget him,” said Emma. “He’s a madman.”

I think we all knew he was more than that—but that’s all we knew. We walked fast in paranoid silence, our brains humming with unanswerable questions. No one mentioned the beggar’s bizarre pronouncements, for which I was grateful. I had no clue what they meant and was too exhausted to speculate, and I could tell from their dragging feet that Emma and Addison were flagging, too. We didn’t talk about that, either. Exhaustion was our new enemy, and to name it would only have empowered it more.

We strained to see any sign of the wights’ bridge as the road ahead sloped downward into an obscuring bowl of fog. It occurred to me that Lorraine might’ve lied to us. Maybe there was no bridge. Maybe she’d sent us into this pit hoping its denizens would eat us alive. If only we had brought her with us, then we could’ve have forced her to—

“There it is!” Addison cried, his body forming an arrow that pointed straight ahead.

We struggled to see what he saw—even with his glasses, Addison’s vision was sharper than ours—and after a dozen paces we could make out, just dimly, how the road narrowed and then arched over some sort of chasm.

“The bridge!” Emma cried

.

We broke into a run, exhaustion momentarily forgotten, our feet sending up puffs of black dust. A minute later when we stopped for breath, the view had cleared. A shroud of greenish mist hung over the chasm. Looming faintly beyond was a long wall of white stone, and beyond that, a high pale tower, the top of which was lost among low clouds.

That was it: the wights’ fortress. There was an unsettling blankness about it, like a face with its features wiped clean. There was a wrongness about its placement, too—its great white edifice and clean lines contrasting bizarrely with the burned-over waste of Smoking Street, like a suburban shopping center plopped in the midst of the Battle of Agincourt. Just looking at it charged me with dread and purpose, as if I could feel all the disparate strands of my silly and scattered life converging toward a single point, unseen behind those walls. That’s where it was: the thing I was supposed to do—or die trying. The debt I had to pay. The thing for which all the joys and terrors of my life thus far had been a prelude. If everything happens for a reason, my reason was on the other side.

Beside me, Emma was laughing. I gave her a baffled look and she composed herself.

“That’s where they’ve been hiding?” she said by way of explanation.

“It would seem so,” Addison said. “Do you find that humorous?”

“Nearly all my life I’ve hated and feared the wights. Across all those years, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve imagined the moment we’d finally find their lair, their den. I’d expected at the very least a foreboding castle. Walls dripping with blood. A lake of boiling oil. But no.”

“So you’re disappointed?” I said.

“I am, a bit.” She pointed accusingly at the fortress. “Is that the best they can do?”

“I’m disappointed, too,” said Addison. “I hoped at least we’d have an army alongside us. But from the looks of it, perhaps we won’t need one.”

“I doubt that,” I said. “Anything could be waiting for us on the other side of that wall.”

“Then we’ll be ready for anything,” Emma said. “What could they throw at us that we haven’t faced already? We’ve survived bullets, bombing, hollow attacks.… The point is, we’re finally here, and after all these years of them ambushing us, we’re finally bringing some fight to them.”

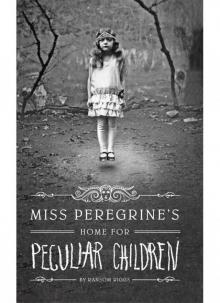

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children

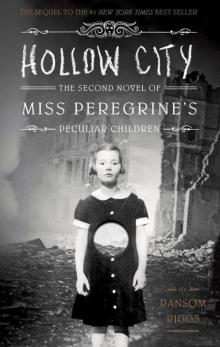

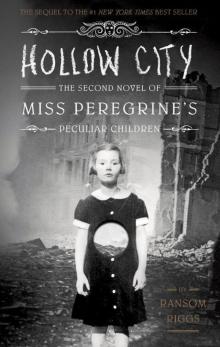

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children Hollow City

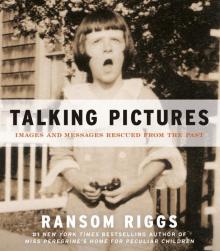

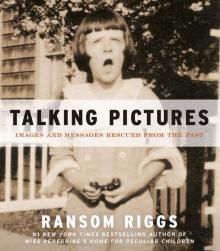

Hollow City Talking Pictures: Images and Messages Rescued From the Past

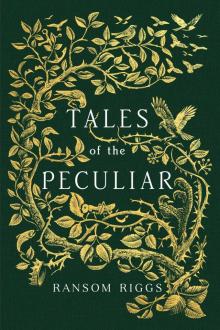

Talking Pictures: Images and Messages Rescued From the Past Tales of the Peculiar

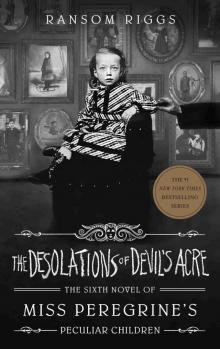

Tales of the Peculiar The Desolations of Devil's Acre

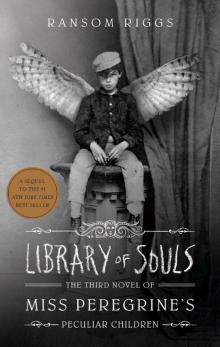

The Desolations of Devil's Acre Library of Souls

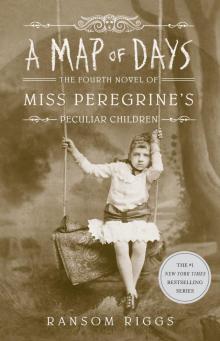

Library of Souls A Map of Days

A Map of Days Hollow City: The Second Novel of Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children

Hollow City: The Second Novel of Miss Peregrine's Peculiar Children Talking Pictures

Talking Pictures